Love Locks and the Memory We Choose to Keep

Love Locks and the Memory We Choose to Keep

DECEMBER 04, 2025

Love Locks and the Memory We Choose to Keep

There's a moment in Total Recall where Arnold Schwarzenegger's character questions whether his memories are real or implanted. It's a concept that felt like pure science fiction in 1990. In 2025, we're living it—and we're doing it to ourselves.

Here's the thing about memories: we don't actually remember moments. We remember the last time we remembered them. Each recall is a reconstruction, and over time, our brains fill in gaps with whatever feels right. Now add photo libraries into the mix. We look at photos to reinforce our memories, and those images become the source of truth. The photo becomes the memory.

So what happens when we change the photo?

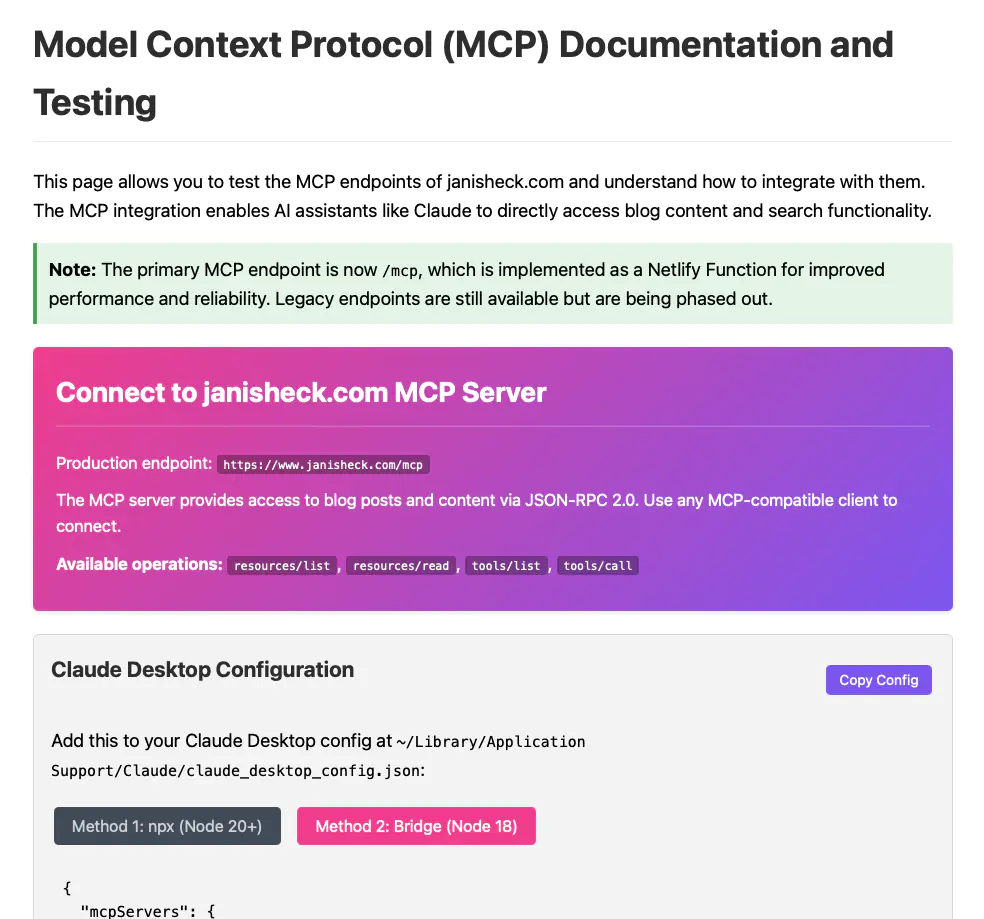

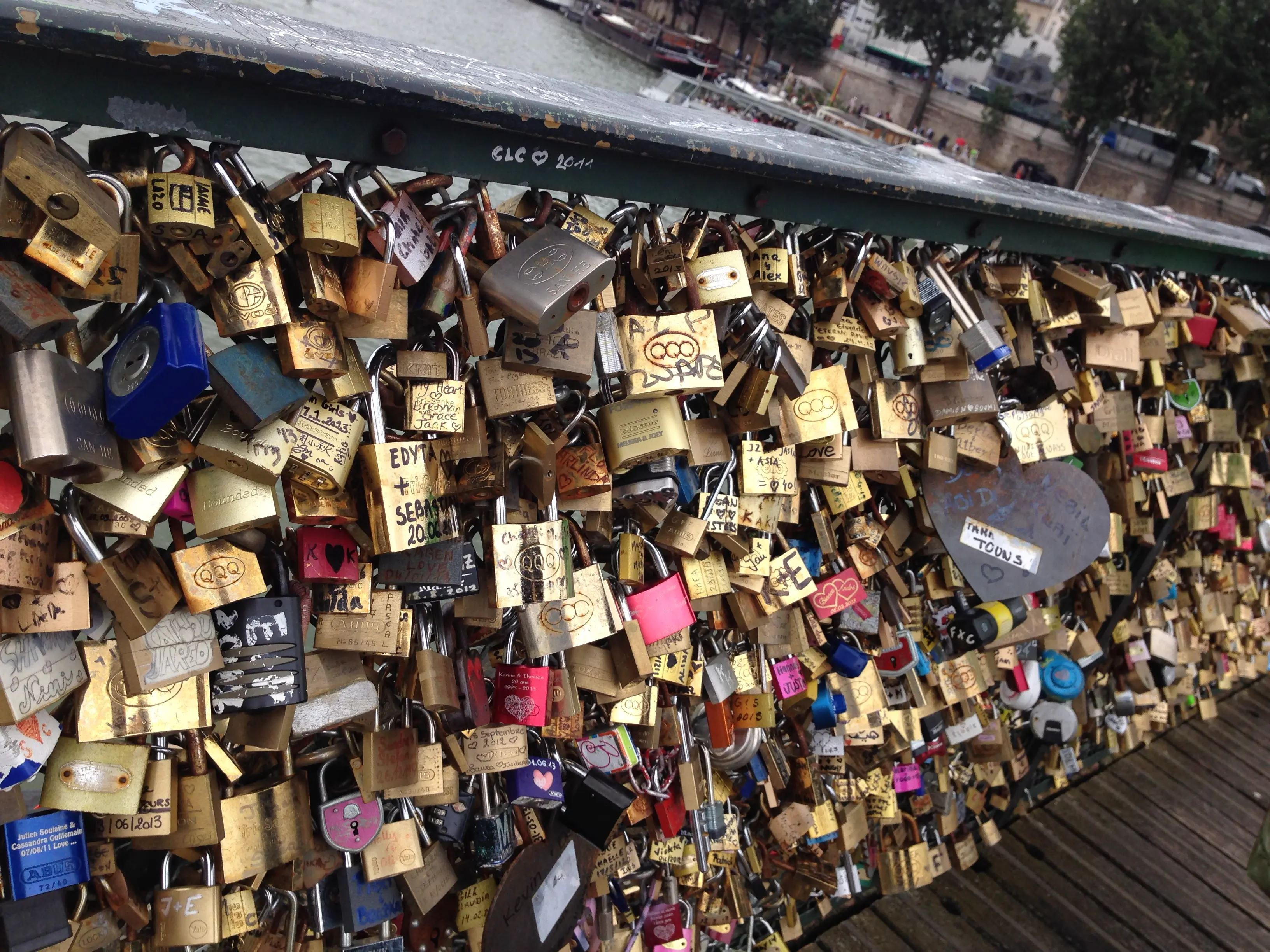

The Pont des Arts

For years, couples would travel to Paris and attach padlocks to the Pont des Arts bridge as a symbol of everlasting love. You'd write your names on a lock, attach it to the bridge, and throw the key into the Seine. Thousands of locks accumulated over the years, the combined weight eventually becoming a structural concern.

I was no different. I wanted to do something special—something a little more personal than a Sharpie scrawl on brass. I had access to a laser cutter at work, and I had an idea: engrave a photo of Melissa and me onto the lock itself.

The Original

This is the photo I chose. Us together. Happy. The kind of moment you want to preserve forever.

The problem with laser engraving photos onto small brass surfaces is that the medium doesn't forgive poor source material or optimistic expectations. The result was... not great. You could tell there were two people on the lock, but just barely. The faces were ghostly, the details lost to the limitations of the process.

But I'd committed. I traveled to Paris, found my spot on the bridge among thousands of other locks, and clicked it into place. Forever. Or so I thought.

Less than a month later, the city of Paris removed all the locks and installed glass panels to prevent new ones from being added. Our lock—along with an estimated million others—was cut away and recycled. The moment was gone before it had a chance to age.

The Revision

I was always disappointed with how that lock looked. The gesture was there, but the execution fell short. So recently, I did something that would have been impossible just a few years ago: I used AI to realize a better version.

Same lock. Same photo. Same moment. But now the engraving is crisp. The faces are clear. It looks like what I imagined it would look like when I first had the idea. This is the lock I wanted to leave in Paris.

I saved it to my photo library. Right there alongside the original.

Which Memory Wins?

Here's where it gets uncomfortable. Five years from now, when I'm scrolling through old photos, which image will I pause on? The grainy, disappointing reality? Or the polished version that matches what I felt in that moment?

Our brains prefer coherent narratives. We naturally gravitate toward the version of events that makes sense, that feels complete. The AI-enhanced photo isn't a lie exactly—the moment happened, the lock existed, we were there. But it's also not the truth. It's a truth I preferred.

And that's the thing about AI and memory now. The tools make it so easy to make subtle tweaks. Not wholesale fabrications—just improvements. A clearer sky. A better smile. A sharper engraving. Each change is small enough to feel innocent, but they compound. The source material drifts from reality, and we don't notice because we're not comparing anymore. We're just remembering.

In the future, it will be harder and harder to know what the original source material even was. Did that sunset really look like that? Was I actually smiling in that photo? Did the lock on the bridge in Paris really show our faces so clearly?

Maybe it doesn't matter. Maybe all memories are constructs anyway, and the photos we keep are just props for the stories we tell ourselves. But there's something unsettling about having the power to edit those props so seamlessly. We're not just remembering anymore. We're directing.

Welcome to Total Recall territory. The question isn't whether our memories are real. The question is whether we'll remember that we changed them.